US

Meet Rev. Andy Bales — The Man Who Lost A Leg Serving The Victims Of LA’s Homeless Crisis

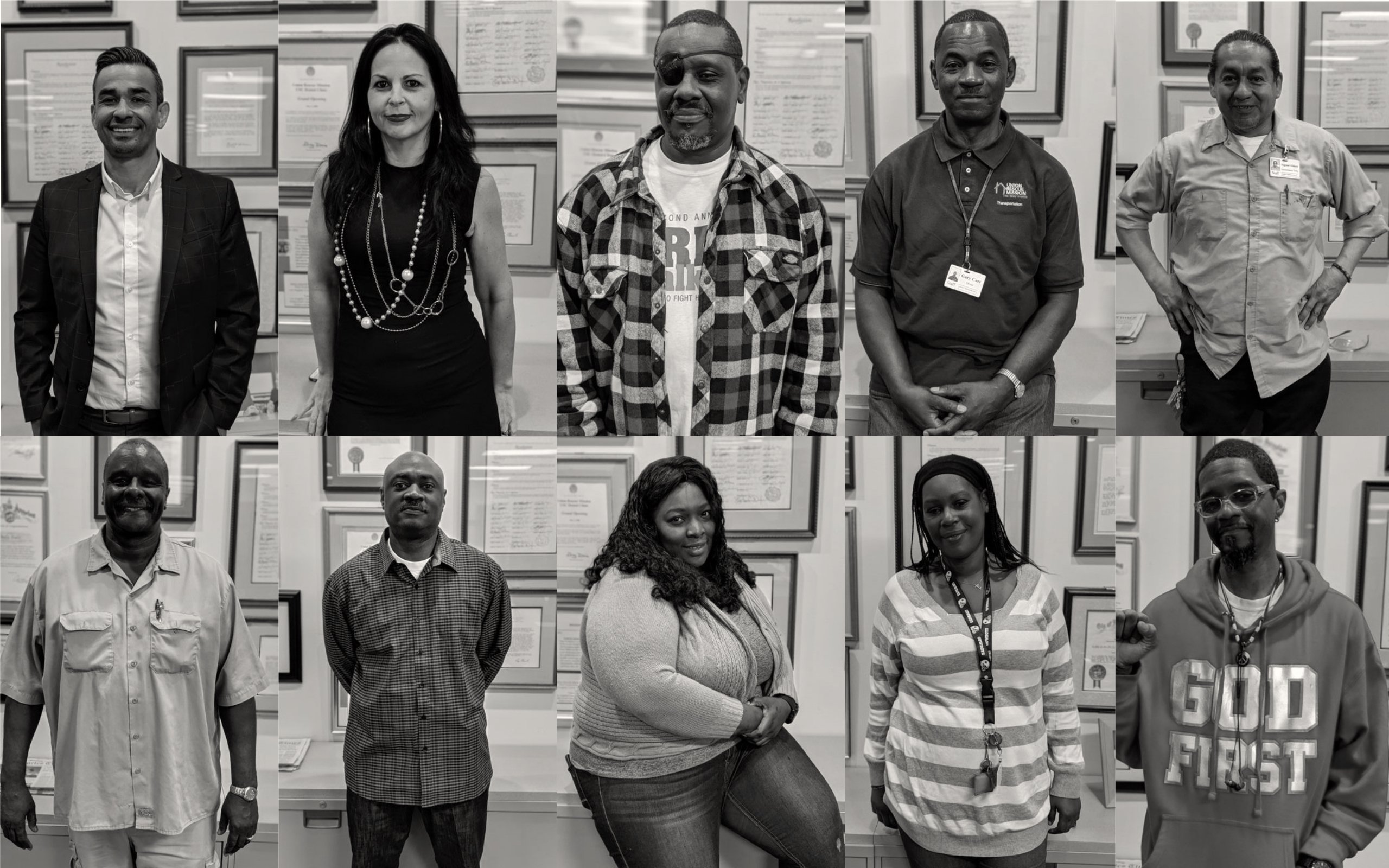

Staff Members of URM/Provided by URM

- Andy Bales, CEO of Union Rescue Mission in LA, lost his leg to infection after stepping in human waste while helping the homeless on Skid Row.

- Medieval diseases like typhoid fever are being carried into the city on rats due to increasing waste management costs.

- He argues that LA county and the city council are not taking productive measures to end the city’s homeless crisis, but his mission is setting an example for government officials.

Rev. Andrew Bales lost part of his leg to a flesh-eating disease he was exposed to in 2014 while handing out 2,000 cold water bottles to the homeless in Los Angeles in 85-degree heat.

Bales, 60, is the CEO of a faith-based, nonprofit homeless shelter and recovery program called Union Rescue Mission (URM) who has dedicated his life to offering support to people affected by homelessness — particularly those who live on the trash-covered streets of Skid Row in downtown LA.

URM Vice President of Emergency Services LaTonja Lindsey has been with the mission for 11.5 years and told the Daily Caller News Foundation that the mission is unlike other shelters in LA because they don’t accept government money and “never turn away a woman or a family.” They are also open “24 hours a day, 365 days a year.”

“I do what I do because I am haunted by the number of people on the streets, and I know we’re making a difference,” the reverend told the DCNF.

Before losing his leg about five years ago, Bales decided to compete in a triathlon five weeks after having a kidney transplant. When he finished the race, he developed a blister that festered into a wound he thought would heal on its own over time. The next week, he was back on the streets of Skid Row handing out water bottles.

“I came in contact with human waste,” he said. “At that time, there were 2,500 people living in a 53-block area, sharing nine toilets.”

For comparison, Bales said nine toilets are about “184 toilets shy of the minimum standard for a Syrian refugee camp.”

He was at the airport a week later, bound for North Carolina, when his foot began to hurt so terribly at that he asked if he could board the plane early. By the time he sat down, he said, his foot was pulsing with pain.

When he landed on the East Coast, blood blisters covered his foot, and by the time he returned to the West Coast from his short trip, he had a 104-degree fever.

Bales admitted himself into a hospital and left in a wheelchair thinking he’d always be in a wheelchair because he couldn’t walk. Another six weeks went by before doctors decided to remove his leg from the knee down. He got his prosthetic leg just days before his daughter’s wedding and still somehow found it in himself to dance all night.

But Bales has a unique connection to the homeless that he’ll never break from — one that has inspired him to dedicate his life to helping those in need.

“I always say I’ve worked my whole life to end up on Skid Row,” he said, adding that it’s natural for him to help people who are struggling.

Bales’ dad and grandfather would jump on freight cars from Des Moines, Iowa, to Compton, California, and other towns starting when his dad was 4 years old until he was 17 and eventually joined the U.S. Army. Bales says the feeling of homelessness never left his father until the day he died.

“My dad’s last week on the face of the earth, he talked about the pain and shame of being a homeless teenager,” he said.

Bales worked as a church and youth pastor before making it to Skid Row. One memory of teaching children at Des Moines Christian School in 1985 has stuck with him throughout his career. While he was teaching a class, a group of kids was picking on one child who “didn’t measure up.”

“I said, ‘Knock it off, and don’t treat someone like that in my classroom,'” he recalled. “But I thought, ‘If this classroom can’t treat a young child kindly, where else can he be treated kindly?'”

The revered saw then that if children can’t receive kindness in a classroom, they certainly can’t receive kindness on the streets.

The next day after seeing one of his students get teased, he read to his class from the Book of Matthew, Chapter 25:

For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in … Truly, I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.

Bales wanted to teach his students that the way in which a human being treats another human being is the way one treats God himself.

The reverend recalled one weekend when he was collecting change at a parking ramp in Des Moines, where he worked 39 hours on weekends. He was watching an NFL game on a miniature TV screen at the time when he heard a knock on the window. He turned to see a homeless man with a scraggly beard, dirty coat and a “bag of soda pop slung around his shoulder” eyeing Bales’ sandwich.

“Sir, can I have your sandwich?” the man asked.

“My immediate response was, ‘I’m sorry, sir, but I need my sandwich,'” Bales said. “And then he just walked away looking so disappointed. I’ll never forget that. It was then that I realized I didn’t practice what I was preaching. Until that time, I kind of looked through people who lived on the streets. Ever since then, I’ve been haunted by their plight.”

A few weeks after that incident, Bales’ pastor coincidentally told him about a downtown rescue mission in Des Moines in 1986 without any knowledge of the internal conflict Bales had been having since his encounter with the homeless man at the parking ramp. In an effort to try to practice what he preached, Bales accepted.

That was 33 years ago. Today, Bales has dedicated his life to helping the homeless through URM on Skid Row.

Skid Row now hosts the largest unsheltered population in the country. Homelessness numbers in Los Angeles County have risen by 12% from 2018 to 2019 with an estimated total of 58,936 people — 44,214 of which are unsheltered — according to a 2019 report by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA).

But attempting to clean trash and provide assistance to the people who live in the area does not come without serious risks as the streets are ridden with disease.

Bales and others trying to help the community get back on its feet have experienced firsthand. He said Skid Row is crawling with bacteria and medieval diseases unique to the area because of its terrible health conditions.

Bales listed the diseases that have come to Skid Row in order:

There’s a special type of [tuberculosis] found only in Skid Row — and it’s a strong, powerful strain. There’s the flesh-eating disease, like I had, which consists of E-Coli, strep and staph. I’ve seen it in other people on the streets. I’ve seen people with a black thumb, losing a leg. When it happened to me, people made a big deal, but it was happening to others long before my situation brought it to light.

There’s also Hepatitis A. All my coworkers have to get vaccinated. It’s quite risky to work where we work. There’s typhus, which is] carried by fleas on rats. Then, the police at the station one block from us got typhoid fever. I’ve only seen that once in Haiti — a little boy in a makeshift house.

Bales also cited Dr. Drew Pinsky, who he said expects the bubonic plague — yes, the Medieval sickness that wiped out millions throughout Europe — this summer, which is also carried into the area on rats and fleas. Pinsky has appeared on Fox News to explain the situation.

“There will be a major infectious disease epidemic this summer in Los Angeles,” he told the network May 23. “We have tens and tens of thousands of people living in tents. Horrible conditions. Sanitation. Rats have taken over the city. We’re the only city in the country, Los Angeles, without a rodent control program. We have multiple rodent-borne, flea-borne illnesses — plague, typhus.”

Democratic Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti blamed this issue on “illegal dumping” by residents and businesses in the city and encouraged people not to blame the homeless.

“People should not dump illegally,” he said earlier in June. “We’re going to prosecute you and go after you if we find you.”

But Bales says the city’s leadership is to blame for the expensive waste management costs that the community cannot afford to keep the city properly maintained.

“Something people don’t mention is that a monopoly was given to waste management companies that have increased fees by 100% or double,” he said. “The amount of waste is exacerbated by dumping fees that people and businesses can’t afford to pay, so they’ve joined in on dumping their waste on Skid Row, thinking, ‘Maybe I’ll get away with adding to the mess.'”

“It’s created a health hazard and a catastrophe,” Bales continued. But he doesn’t blame Garcetti personally.

“The mayor and the city council allowed the monopoly of waste management and an increase in fees. I don’t blame Garcetti,” he said. “I don’t single him out and say he needs to resign, but the whole thing needs a whole new level of leadership that treats [homelessness in LA] like the crisis that it is.”

While trash piles due to expensive waste management costs, the homeless population continues to increase due to skyrocketing rent in the area. The median rent for a one-bedroom apartment in 2019 was $1,370 in September, and the price of a two-bedroom rental was $1,760, according to a rent report from Apartment List. In the third quarter of 2013, the average monthly apartment rent price was approximately $1,480 — a $30 monthly increase from the third quarter of 2012, HUD reported in 2013.

Some of LA’s residents who could afford to live here ten years ago can no longer do so.

A lot of the homeless in LA are “people of means” who “are losing their places to live, who move to their cars, who are lonely — and that begins the destruction of their lives,” Bales explained. “That’s part of it. People are escaping into drugs and alcohol rather than continuing to fight.”

But unlike other big, mild-weather cities, Bales said there’s no place providing less help than LA.

URM is trying to combat that problem with a team that has the unique experience necessary to serve those that are seeking help. Twenty-five percent of the staff has, at some point in their lives, experienced homelessness and participated in URM’s year-long recovery program themselves. They are people who have been affected by homelessness, either directly or indirectly, and want to help others do the same.

LaTonja Lindsey was homeless for a time before being hired by the mission.

“I myself was homeless for a time,” she said. “I lived side-by-side with women I wouldn’t [have] ordinarily been around. The experience humbled me and opened my eyes to who and what homelessness is. In the words of Andy Bales, ‘He/She isn’t homeless, he/she is experiencing homelessness.'”

URM Vice President of Programs Joy Flores says she joined URM in part after her brother died at age 30 due to the toll homelessness had on his mental and physical health.

“My older brother struggled with multiple diagnoses,” she told the DCNF, “and although had seasons of sobriety and success, after years in and out of treatment centers, living on the streets, halfway houses, etc., his self medicating tendencies got the best of him at the age of 30, and he died on the streets, just blocks from URM on Pico Boulevard.”

“Although the world might try and label our brothers and sisters who are living on the street, I see beautiful souls who are in need of love, forgiveness and tools to help them get free,” she said.

Kitty Davis-Walker said she was “very apprehensive at first” to work at URM.

“I do not like to see people in distress,” she said. “I thought I would be crying every day, but God spoke to my heart through tears and prayers about coming to work on Skid Row, and He said, ‘I am making you part of the solution.’ So I said, ‘Okay, Lord, send me!’ Doesn’t mean I don’t cry, but I don’t cry every day! It is truly a blessing to help and serve all the men, women and families God has entrusted in our care.”

URM has helped “thousands” out of homelessness by offering support from people who have experienced the same devastation and were able to change their lives. The focus of the mission does not revolve completely around housing and comfort but recovery and change. Believing that people can change is what separates URM from other shelters and government programs.

New York puts a roof over 95% of homeless people, while LA has 75% on the streets and only shelters 25%, the LA Homeless Services Authority reported in 2019. The Homeless Shelter Directory lists about 80 homeless shelters within a 33-mile radius of downtown LA.

“I believe in recovery,” Bales said.”[The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development] and other housing services only believe in providing expensive housing units.”

“From the start, we invite people to enroll in a year-long intensive recovery program,” he explained. “Our staff welcomes everyone with open arms and the passion of Christ. We offer classes on grief and loss, overcoming addiction, relationship building, Bible studies and then we have graduation at the end of the year. We also have a family center with a similar program for moms, children and senior ladies.”

Women and children make up 40% of the homeless population in the U.S., according to a 2018 HUD report, which is why URM developed a family center called “Hope Gardens” in Sylmar, California, on 71 acres of land, which aims to help women and children out of homelessness within 12 to 36 months.

Comparatively, Bales says HUD, LA County and the city council believe more in providing shelter than they do in encouraging life transformation.

“They’ve given up on transformational housing,” Bales said. “They don’t fund us and we don’t want to be funded by them because of their restrictions.”

One of those restrictions is the implementation of the “harm reduction model,” which Bales calls the “harm-causing model.” The harm reduction model allows those seeking shelter to keep using drugs and alcohol in an effort to “meet drug users where they’re at,” according to the Harm Reduction Coalition website.

While HUD does not require harm reduction, use of the model is “incumbent on federally funded Continuums of Care, which are local coordinating bodies for homeless services, to allow emergency shelters to utilize ‘low-barrier’ practices. Low-barrier practices may include allowing individuals to access services without preconditions for abstinence from substances,” Assistant Professor of Clinical-Community Psychology at DePaul University Dr. Molly Brown told the DCNF.

“Simply allowing access to services is only one aspect of harm reduction,” Brown explained. “Harm reduction is an individually tailored approach to intervention that gives people choice and agency in self-determining their goals to remain safe and improve their quality of life, which may or may not include cessation from substance use.”

California HUD Regional Public Affairs Officer Eduardo Cabrera, who spoke highly of Bales, told the DCNF that harm reduction is incentivized through the way the government allocates funding for homelessness, which depends on local Continuums of Care. It also depends on the government’s Housing First model, which puts shelter before anything else.

“[HUD’s] Housing First emphasis is not new,” Cabrera explains. “To put it most simply, there’s no support a homeless person needs that can’t be given after a homeless person has housing. If you put the solution of permanent housing on the front-end and then tailor support to [a homeless person’s] needs, you can work toward self-sufficiency. …For the chronically homeless, this intervention is what works.”

Cabrera also says it’s the government’s most cost-effective way to help the homeless.

Brown says the harm reduction model reduces “utilization of costly emergency services. When adequate overdose prevention resources are available within homeless services, lives can also be saved. … There is substantial harm done to individuals when their right to a safe place to stay is denied due to having a substance-use-related disability.”

Bales, however, argues that the Harm Reduction Model “is empowering people to die.” While URM does not turn away those who are experiencing homelessness in part because of a drug or alcohol addiction, his mission does take an abstinence- and faith-based approach once members take part in its year-long program.

The mission’s staff meet and work with people in person. It feeds 3,500 meals a day to its guests and guests from the outside; it providing showers, clothes and blankets; its staff go out on the streets to hand out cold water when it’s 85 degrees or over, like Bales was doing the day he came in contact with the disease that attacked his leg.

URM also works with a number of local universities to provide legal, mental health, nursing clinic and dental clinics. There are chaplains also readily available to teach and practice faith as part of URM’s program.

The mission is comprised of 180 employees and 3,000 volunteers that help serve 1,250 guests under one roof, and 250 more at Hope Gardens. Soon, Bales says, the number at Hope Gardens that will be 300.

Visit URM’s website to find out more about the mission and its team and what they do, as well as how to donate, volunteer or fundraise. Bales also recommends watching the short documentary “Paradise Lost” by Komo News to get a better sense of the homeless crisis taking over Skid Row.

The LA city council and county offices did not respond for comment in time for publication.

All content created by the Daily Caller News Foundation, an independent and nonpartisan newswire service, is available without charge to any legitimate news publisher that can provide a large audience. All republished articles must include our logo, our reporter’s byline and their DCNF affiliation. For any questions about our guidelines or partnering with us, please contact [email protected].